This course has enabled me to deepen my understanding of my role as a teacher librarian (TL). What I have valued above all else is that the course has had practical applications.

Our school caters for kindergarten through to final year secondary students (ages 3 – 18). We have four principals and two deputy principals along with three coordinators for each of the International Baccalaureate programmes we run. I have struggled relating to all of these leaders and tried to have them work through the one principal responsible for the library. After reading the course work and creating a blog post about principal support I have come to the understanding that I need to be communicating a clearer message about how the library supports their goals for the school. It is clear that these administrators did not understand how a TL can work with colleagues to enhance student learning outcomes. Often the work of the teacher librarian is invisible to administrators as the role itself is to work to empower others (Hartzell, 2002. p. 2). Two actions I have taken to garner support from the principals have had positive results. I created a library plan for the rest of the year and linked the goals to specific goals in the school strategic plan. Two weeks ago we all met and discussed the plan. The principals have endorsed it and will communicate it to staff. I also began a monthly report about the activities of the library using three headings – successes, challenges and opportunities. I sent the report to the principals and also posted to our library web page. Instead of reacting to all of the differing demands of the principals in our school, the library plan and the reports have opened positive dialogue so we can find ways to work together to further improve student learning outcomes.

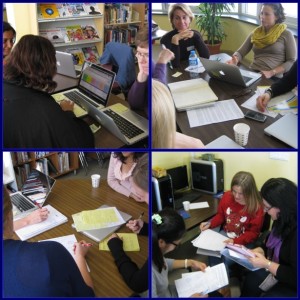

I was challenged by Ken Haycock’s assertion that “Collaboration is the single professional behavior of teacher-librarians that most affects student achievement,” (Haycock, 2007, p. 32). I could see that I was mostly operating at coordination and cooperation levels while I wanted to develop collaborative partnerships that included integrated instruction and integrated curriculum (Montiel-Overall 2005, p.34). I could relate to the frustrations my classmates shared on the forums. I understand that collaborative environments are complex and those who work in them require flexible and resilient personalities (Brown, 2004, p.13). Our school has one third of the teaching staff change each year, not an uncommon thing for international schools. This means that I have to quickly establish positive working relationships with my colleagues. By working effectively in the coordination and cooperation roles I am confident that this will build trust with colleagues and enable us to go on to integrated instruction and curriculum design together. Last week I completed an integrated digital story telling unit with grade 3. I planned with the teachers, we team taught the unit and now we are in the process of giving feedback to the students. My colleagues and I are producing a video to document our collaborative work and celebrate the student learning successes.

While investigating the different models of information literacy I changed my mind about the value of adopting a single model for the entire school. I had given up trying to encourage my colleagues to adopt a school-wide information search model as I had met with so much resistance in the past. People had their own models or they used pathfinders. I now see the need for adopting a specific model as students need to use it with different subjects and over a period of time to be able to use it effectively as a research and metacognitive tool (Wolf, Brush and Sage, 2003, p.14).

One of the ways to influence colleagues to change their minds is to use evidence based practice to show the value of a strategy. I have started to use Kuhlthau’s Information Search Process (ISP) with grade 11 for their Extended Essay and I am collecting evidence by asking them to complete the reflection sheets as outlined in the School Library Impact Measurement toolkit (Kuhlthau, Todd and Heinstrom, 2005, p. 16). By using this data and published article in journals I can show my colleagues the value of using one model to assist our students in becoming information literate.

Through this course I have changed my mind, evaluated my effectiveness and taken action to add depth and value to my role as Teacher Librarian.

References

Brown, C. (2004). America’s most wanted: teachers who collaborate. Teacher Librarian, 32(1), 13-18. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com (AN 14658045)

Hartzell, G. (2002, June).What’s it take? Paper presented at Washington White House Conference on school libraries check out lessons for success, Washington. Retrieved from http://www.laurabushfoundation.com/Hartzell.pdf

Haycock, K. (2007). Collaboration: Critical success factors for student learning. School Libraries Worldwide, 13(1), 25-35. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com (AN 25545933)

Montiel-Overall, P. (2005). A theoretical understanding of teacher and librarian collaboration (TLC). School Libraries Worldwide, 11(2), 24-48.

Todd, R. J., Kuhlthau, C. C., & Heinstrom, J. E. (2005). School Library Impact Measure S*L*I*M A toolkit and handbook for tracking and assessing student learning outcomes of guided inquiry through the school library. Retrieved from http://cissl.rutgers.edu/images/stories/docs/slimtoolkit.pdf

Wolf, S., Brush, T., & Saye, J. (2003, June). The Big Six information skills as a metacognitive scaffold: a case study. Retrieved from American Association of School Librarians website: http://www.ala.org/aasl/aaslpubsandjournals/slmrb/slmrcontents/volume62003/bigsixinformation